How to Make a Graphic Novel

How to Create a Graphic Novel

So you want to make a graphic novel (GN). But you wonder — how can I do this? Do I need to buy a $300.00 graphic novel kit? No. You don’t! Unless you want to buy one.

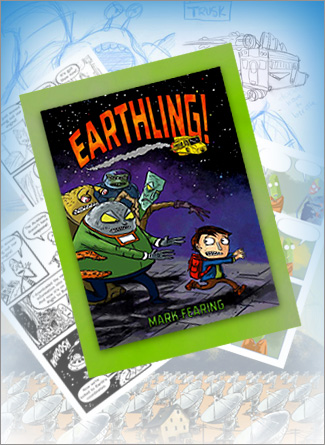

Here’s how I made my graphic novel, Earthling! which was published by Chronicle Books. There are many ways to make a graphic novel and you need to find what works best for you. But if you are interested, spend a few minutes reading about all the mistakes I made. I mean - see how I did it.

Earthling! is a big book (240 pages!) because it's an epic narrative. The nature of the story means there are lots of locations, characters and action. Lots of locations means you have to design and draw a lot of different places. And with lots of characters you spend a lot more time designing and drawing different characters while keeping them 'on model' (looking the same). So one way to make a graphic novel simpler is to cut back on the number of unique characters and locations.

My production process for Earthing! had five phases -

I wrote the entire story in comic book/screenplay format. The goal was to produce a manuscript that was as easy to read as possible without seeing drawings. I included scene headings, transitions and included plenty of action description to explain what was happening visually in the story and shown on the page.

I revised the manuscript with editor feedback until it was considered final.

I then drew page roughs (often revising the script in small ways to meet the needs of the final layout).

I placed these rough drawings into Adobe Illustrator and placed all the text (this makes it easy for an editor to review).

Only after a final review did I start final line art and painting (Photoshop).

By writing the entire story first in script format we are able to concentrate on the narrative making sure that the big issues resonate and the characters are as fully formed as possible, without being distracted by a drawing. It makes it easy for editors and others not accustomed to GN’s and comics to review the story (plot, character motivations and pace). But editors need to understand that the script MAY change when I start drawing. The script has to be in service to the final illustrated format.

Now The Details…

1.

Working with my editor at Chronicle Books, I wrote the entire story in screenplay format. Well, a sort of comic book-screenplay hybrid format. The point being anyone could pick it up and read the STORY and PLOT and understand it. They didn’t need to know about comics, or graphic novels or panels on a page. They could read and comment on the STORY. That’s the important part isn’t it? No matter what format the material is in.

We edited the manuscript/script many, many times. And for those who dislike the editing process I am happy to report that Earthling! got better each time.

The structure simplified over time and with my editor’s help I cut elements that didn’t make sense or support the story. During this time I did some rough character designs and did lots of sketches of locations and elements in the story.

A bit of a side note here — I wouldn’t recommend this method to GN projects where the author isn't experienced at writing for comic books. Because I am both drawing and writing it, and I have experience with panel-style stories, I start by writing to take advantage of ‘the page’ so to speak. And I know my limits as an artist, what I do well (character acting, funny characters) and what I don’t do well (serious looking sci-fi technology). I can write the story while seeing it on the page in my head and knowing (hopefully) how I will be drawing the action.

2.

So after many months of editing and revisions we arrived at a final manuscript. At least a manuscript that the editor felt made sense from a story and character perspective. Or she was tired of seeing my revisions!

At this point I started doing roughs. I draw roughs on 11 x 17 paper, with a full spread (two pages). The book is approx 6 x 8. So I can do these rough/thumbnails in the right dimension…or almost the right size. I scribble in the text as I draw in rough balloon shapes and I get an idea where I have written too much, or where a scene doesn’t fit into a page as I thought and goes on too long. So this phase also has some editing in it.

I draw each page two or three times, usually. Sometimes I can nail a simple page in a single rough. But often I end up drawing several versions, redraw some panels, or change the composition of the page and redraw. Then in batches of 20 or 30 pages, I scan them in. Then I can pick and choose from the various roughs to create a ‘final’ page.

3.

Any given page may be made up of roughs from three or four different pieces of paper. I get to craft the page from the drawings I think work best.

This ‘rough’ is now in high resolution and slightly larger than print size.

Then I create a print resolution (300 dpi) Photoshop file of the rough art, and import that into an Adobe Illustrator file that is set up for print (proper bleeds, ETC). There I add the balloons and type.

4.

Sometimes I find a problem where the art didn’t leave enough room for the type and I have to draw a new rough, or make some changes in Photoshop and reimport the revised rough drawing into Adobe Illustrator. When all the type is in, this Adobe Illustrator file can be exported as a PDF for the publisher to review. So they have rough art AND final copy to review.

5.

It’s important to note that in the drawing phase, the script will continue to change. This is what makes a graphic novel unique compared to a prose book. The manuscript you write has to work on a drawn page. It’s similar to a film in that the final product is not the final written script. It’s the film that comes from it.

During the art phase I rearranged character’s dialogue, I cut one character entirely, I cut scenes and have writen new dialogue to end a chapter or compliment a drawing that pushed the story in a slightly different way. Sometimes my writing just came up short when paired with the art and some dramatic scenes ended up needing far less dialogue when the art was there to carry gravitas.

Once the editor gave a final sign-off on pages, I import the type layer back into the high res Photoshop file with the "original" high resolution rough drawing and draw the final pen line art.

6.

In Earthling’s case the pages then went to artist extraordinaire Ken Min and he colored most of the book. So as I was drawing final art, he was coloring. I wold sometimes color a first page of a chapter if I had certain colors in mind. But often I was too busy trying to draw the final art and Ken took the lead.

7.

And here is a final page with crop marks.

Ultimately the script has to mesh with the drawings. They work together to tell the story. Drama comes not only from the pursuits of the characters but also the composition and visual pace set on the page. It is a back-n-forth process, not a writer writing a final script that can never be altered. The writing informs the decisions of the artist and the drawings impact the story. This process often produces its best results when the writer is also the artist, but teams often create wonderful work as well.

I hope this was infomrative, helpful or inspiring. Making a GN is one of the most satisfying projects I’ve ever worked on. But it requires patience and a willingness to revise and edit your work until the very last line is drawn, face colored and comma placed. Have fun!

Would you like to dig into an additional Earthling! story? Click here to read an online comic book set in the Earthling! universe!